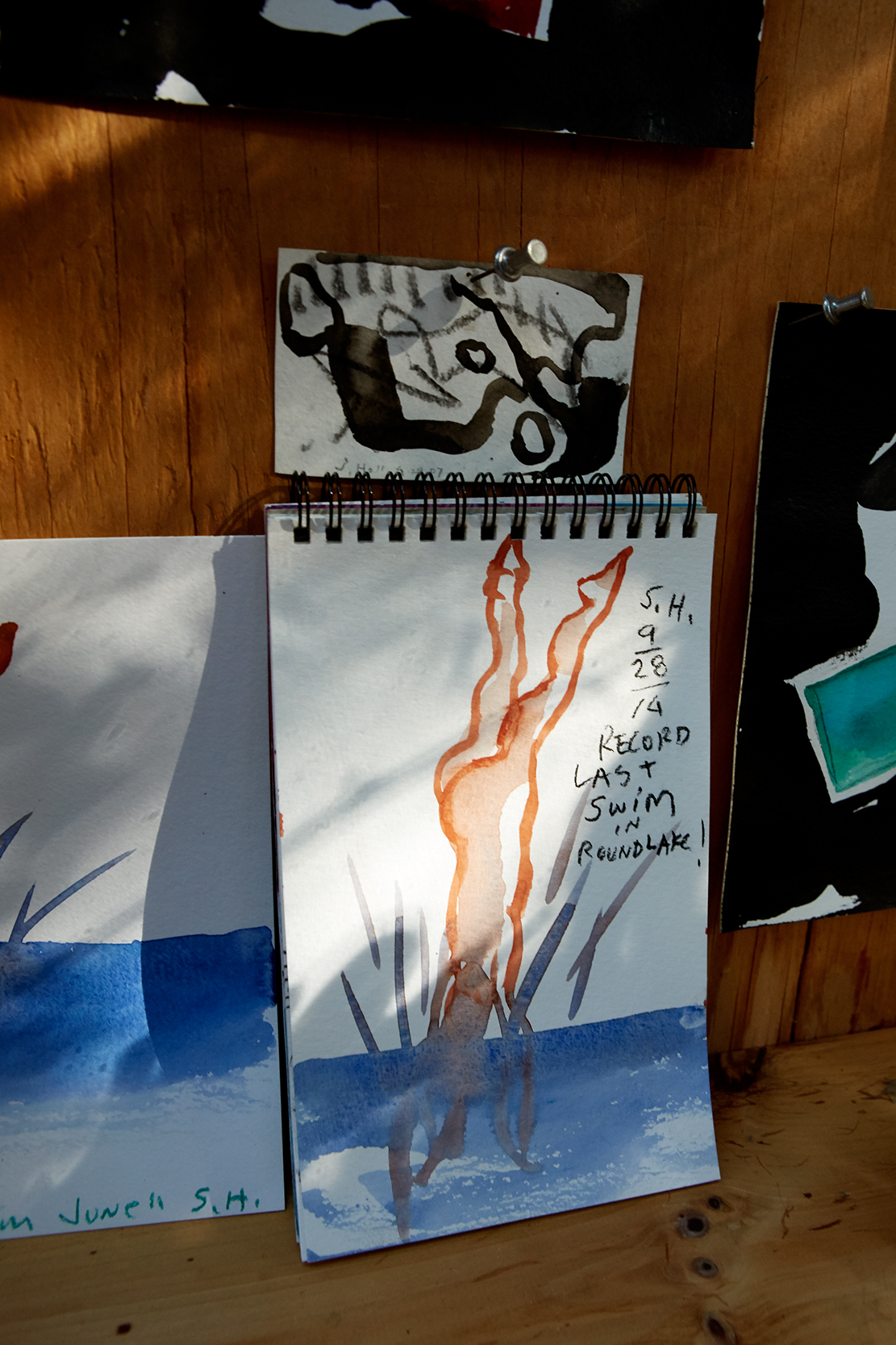

“It’s dawn at a small, tranquil lake in a wooded corner of northern Dutchess County — more of a pond, really, bordered only by a few houses on rustic plots. The water is still; the sky is bright with birdsong. In a small hut, mere steps from the shore, a white-haired man sits at a simple wooden table making watercolor sketches. Surrounding him on the walls of the hut are dozens of sketches he has done here on previous mornings — some geometric in feel, others more organic, several more inscribed with lines of poetry, like these from John Ashbery, on a sheet depicting the arc of the passage of the sun or some other celestial orb:

‘The summer demands and takes away too much.

But night, the reserved, the reticent, gives more than it takes.’

Silently, the man paints. There is no phone or computer. Then he puts away his brushes, leaves the hut, and follows the path back up to his house, not far away. Later that morning, he will be sitting in his New York office a hundred miles south of the lake, supervising the design of buildings to be built or proposed on major sites on most of the world’s continents. In the office are more watercolors — sheaves of them — along with architectural drawings and models. While exploring issues of form and composition with the curiosity of an artist’s mind, many of the watercolors echo an inscription I found written in pencil on one of the raw plywood walls of the lakeside hut, when I was invited inside it, later that day: ‘The Zen sense of the alone’

We were at the T2 Reserve, a rocky, 30-acre forested preserve in Rhinebeck, New York, which was recently created by architect Steven Holl, the man from the hut. After several minutes amidst the greenery my friend and I found ourselves delighted by the seductive way in which the path gently reveals itself in front of us, moment to moment. Not with the primal logic of an ancient Indian trail, insinuated centuries ago into the landscape’s dips and rises, like so many other paths in upstate New York. Nor with the Cartesian clarity of a now-abandoned road that was carved out for motor vehicles in the 1920s, still discernible even after new greenery has encroached upon once-clear path. And certainly not with the elegant definitude of a Zen garden walkway, where, with elliptical grace, a string-wrapped stone on the ground might signal, ‘Not this way, that way.’ No, the directional signals to be found in the T2 Reserve reflect the esthetics governing Holl’s architectural work in general: sophisticated but subtle and unpretentious, and all about the rich possibilities any of us can find in the simple experience of being alive — walking through the woods, looking at nature, breathing deeply, gratefully; thinking in a relaxed way about nothing and everything.

‘I made the path with my landscape designer,’ said Holl, whom Time magazine once called America’s best architect. ‘It was a sculptural cut. We only needed to clear a few trees.’

The land from which Holl created the preserve was once slated for subdivision into five suburban residential plots. Holl bought the land and turned it into what he calls an experimental topological landscape.

‘The last thing we needed here were more McMansions’” he said.

Visiting this place, it’s impossible not to get a strong sense of the motivating energies — the hopes, beliefs, convictions — that imbue Holl’s work with such humanity. His museums, galleries, libraries, performing arts centers, and other works are widely noted for gratifying both spirit and mind. ‘Architecture is bound to situation,’ he has written. ‘And I feel like the site is a metaphysical link, a poetic link, to what a building can be.’

Entering Holl’s world means more than embracing Nature with a capital N. It means giving yourself back to your own human nature apart from screens and media and a frame of mind often too distracted — actually, too constricting — to allow the deepest kind of breathing that human bodies are capable of.

Architects may be known for manipulating materials like stone, glass, and steel in the creation of structures we can successfully live and work in; and good architects inspire us, too. But the best architects, like Holl, also create places that help amplify not only cogitation and inspiration, but, indeed, respiration itself…”

– Stephen Greco

Read the full article at Upstate Diary.

Photos © Kate Orne